Arielle Bennett, Programme Manager, The Alan Turing Institute, UK, and Esther Plomp, Data Steward, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands

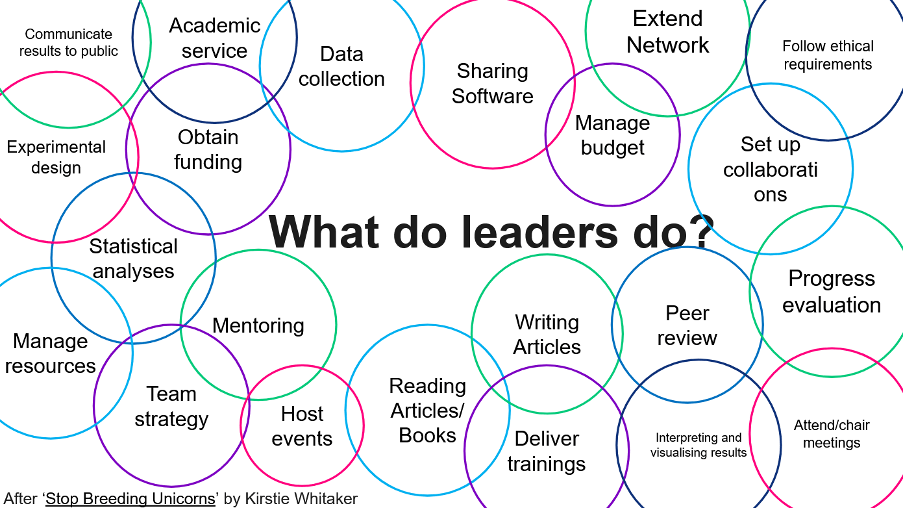

Leaders in research are commonly performing a lot of different tasks, as highlighted in this slide from our recent REDS Conference presentation below:

Currently, we expect our research leaders at universities to be great at all these tasks, all of the time, and on their own: each Principal Investigator would have to be a genius to manage all of this (Elkins-Tanton, 2021).

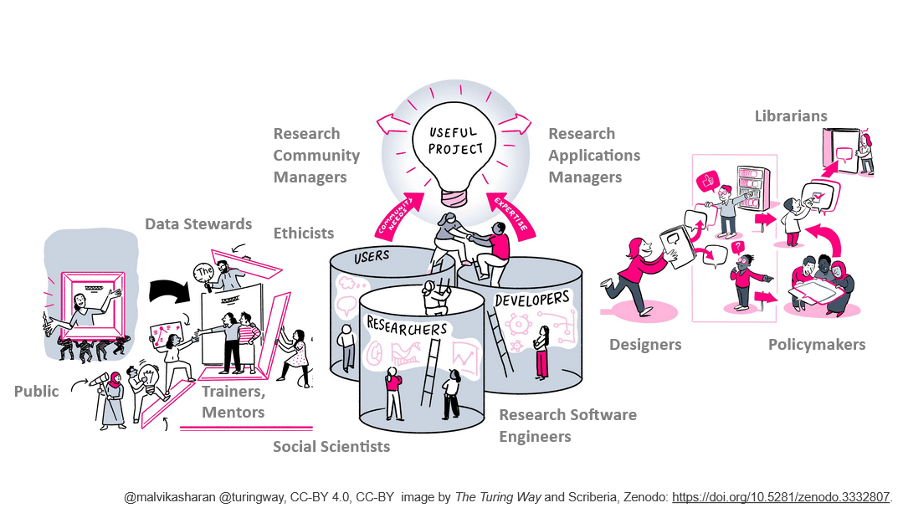

In practice we know that it is impossible for a single individual to manage all of these tasks, and there are a lot of other individuals involved in research that are already doing this work, such as Data Stewards, Research Software Engineers, Community Managers, Lab Technicians, Project Officers, and so forth. We like to term these roles ‘Team Infrastructure Roles’.

Recent policy developments have focused increasingly on the inclusion of these types of roles in the research environment, as this aligns well with the broader discourse around both research culture and reproducibility. In the UK, the government’s R&D People and Culture Strategy, published in 2021, specifically raised the issue of ensuring that assessment of and incentives in research take into account everything that contributes to excellent research and innovation, and therefore to take the focus off grant winning PI academics as the main (and only) element of research to measure and reward:

“We need to ensure that assessment and incentives take into account everything that contributes to excellent research and innovation…

…This will help to diversify career pathways, particularly in academia where there is too often a focus on the individuals who lead research teams”

This is also reflected in the UKRI People and Teams Action Plan of 2023: “We will ensure that our institutional level assessment, and our funding application and assessment processes incentivise the development of the R&I workforce by encouraging a diversity of career pathways and supports a positive culture that yields high quality research and innovation outputs.”

It is also discussed as part of the recommendations from the Reproducibility and Research Integrity report from the UK’s Science, Innovation and Technology Committee in 2023, where one of the conclusions was that ‘Funders and universities should develop dedicated funding for the presence of statistical experts and software developers in research teams. In tandem, Universities should work on developing formalised, aspirational career paths for these professions.’

Our view of who research ‘leaders’ are therefore needs to be adjusted as well, so that the focus is less on the sole genius PI, and more on how a team can function well so that they can appropriately address the research questions they are working on collaboratively. Our recent work has focused on highlighting the many roles in research teams that can specialise in certain areas so that individual PIs do not have to take care of all the tasks in research.

How does this look in practice?

We turn to our own roles to highlight examples of leadership in research:

Esther is a Data Steward at the Faculty of Applied Sciences at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. In addition to supporting researchers with their daily hurdles and questions regarding data management and Open Science, she is demonstrating leadership skills by being involved at a strategic level. Her efforts contributed to Open Science being foregrounded in the Faculty Strategy. She also coordinates a Faculty Open Science Team, which ensures that the perspectives of all the departments are taken into account in any future steps taken. Alongside this, she is also taking leadership roles in Open Science initiatives that go beyond the faculty, such as working groups of The Turing Way and co-founding the Open Research Calendar. These developments and initiatives are not normally a part of a researcher’s responsibilities, but without them less progress would be made to achieve the goals of the Faculty, and the impact of work done in the faculty would be very limited to the institute itself.

Arielle is a Programme Manager at The Alan Turing Institute. Alongside the technical and policy skills required to deliver programme activities on time, to budget, and in line with organisational and funder requirements she also takes on leadership roles in team culture. She’s a proponent of working more openly across teams, including sharing templates and resources where feasible. She’s also a core contributor to The Turing Way, part of the Book Dash Working Group (a Book Dash is an intensive way of producing collaborative writing), and she mentors other open researchers looking to set up their own open source projects as part of Open Seeds. Without organisational buy-in, she’d never be able to participate in the different projects, which are key channels for dissemination of open source principles and approaches.

We have addressed opportunities for cultural change in more detail in a recent research article: A Manifesto for Rewarding and Recognizing Team Infrastructure Roles (Bennet et al, 2023). In this article we discuss efforts that can be made, as a result of the growth in Team Infrastructure Roles, to tackle emerging challenges. We summarise our recommendations here below:

For these roles to thrive in the research environment we need to start formalising the way that Team Infrastructure Roles are included in the research environment, and consider pathways for career development so that these individuals can thrive and further progress.

On a bigger scale, including these roles in the research environment includes broader structural changes in the global research system that are beneficial for the research ecosystem as a whole:

- Expand the recognition of contributions to research. We need to move from solely considering first and last author positions on research articles, to a more holistic system of acknowledging contributions from different people. Current initiatives like the CREDIT taxonomy are going some way to addressing this, but academia is still very much focused on ‘peer reviewed publications’ as the predominantly valued research outputs which hampers these efforts.

- We therefore also need to go beyond the recognition of authors or contributors of research articles. There are many other research activities that do not lead directly to commonly measured outputs such as research articles. These activities can include datasets or software repositories that are shared, or community building or training efforts that focus on improving transparency, reproducibility and cooperation, critical to accelerating scientific process.

- Once these contributions are considered in research assessment, we would also need to consider how these contributions are evaluated or controlled for quality. Similar to peer review of articles, a system could be established for expert review of all research outputs, using the experience and skills of Team Infrastructure Roles in this process.

If you are interested in discussing this further, we maintain a Slack channel in the Turing Way Community to stay connected and exchange ideas. Email theturingway@turing.ac.uk to join the Slack channel, or swing by GitHub: The Turing Way.

Leave a comment