By Dr Martina Diehl, Academic Development Advisor, Sarah Dodds, Digital Learning Advisor, and Dr Peter Whitton, Senior Academic Development Manager. All authors are based in the Durham Centre for Academic Development (DCAD), Durham University, UK.

Creative communication has always been at the heart of research work, both internally as a way of generating and testing new ideas, and externally as a way of disseminating findings in a meaningful way.

Contemporary ideas of researcher development highlight communication as a fundamental research competency (Vitae, 2025; Hoving, 2023; Coon et al, 2022) and being able to use a range of techniques to communicate ideas is seen as key to engaging with diverse groups, including policymakers and the public, showing broader impact (Cooke et al., 2017). Through engaging in a variety of dialogues, researchers can make and shape meanings creatively and critically, and with that become more aware of their place in the world, with the world and with each other (Freire, 1996). A creative dialogic approach enables researchers to think about their audience early in the research process and can help with meaning making and exploring their research through different lenses.

In this post we will explore the Durham University Researcher Development Programme’s ethos of playful learning (Nørgård, Toft-Nielsen, and Whitton, 2017) and creative communications as core values.

Why creative communication is important

Despite calls to reform research assessment processes to better foster quality, creativity, and open research practices (Wilsdon et al., 2015; Hicks et al., 2015) the emphasis for researchers remains on the product – research output – rather than the process – research journey.

The Durham Centre for Academic Development (DCAD) Researcher Development Team puts the value of failure, experimentation and critical reflection at its core, and aims to create a healthy and vibrant research ecosystem with a playful approach so that researchers feel encouraged to take risks, and to engage in novel and long-term projects they are passionate and motivated about, as opposed to focusing on research projects with more predictable and quick outcomes. Encouraging creative and critical research, we are flipping Ball’s (2012) notion of ‘performativity’ on its head by focusing on experience, rather than solely on the product.

On the programme we emphasise reflection and (inter)active learning opportunities to provide participants with time and space to prioritise meaningful development.

Researcher development in playful context

DCAD, provides support for staff and students in enhancing their teaching, learning, and research practices. Much of DCADs original ethos originates from the founding Director’s research into playful and game-based learning (Whitton et al, 2025; Nørgård, Toft-Nielsen, and Whitton, 2017 ) and many of the staff contribute to the Playful Learning Association’s conference and The Journal of Play in Adulthood and embed playful practices in their teaching and learning design activities. The fundamental principles of playful learning are:

- Meaningful experiences:

- Intrinsic motivation

- Failure Mindset

- Lusory community

- Imaginative freedom

In a researcher development context this means that it is essential that workshop participants can see the link between the playful activity and a desired outcome (for example improved communication skills, confident networking); that they have a desire to participate in the activities for their own sake rather than for any extrinsic reward; that workshops happen in a safe and supportive space where mistake making is viewed as an inevitable part of the learning process; that participants immerse themselves in development tasks, learn collaboratively and are open to new possibilities and experiences.

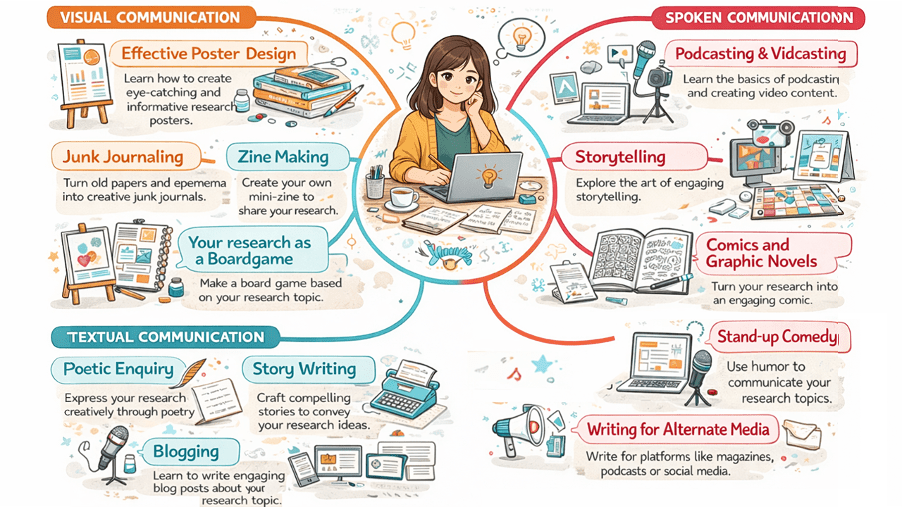

An important part of the DCAD researcher development ethos is an emphasis on the ‘process aspects’ of knowledge building and investigation with a particular focus on narrative creation, media exploration and language-play (see Figure 1).

To exemplify this, we have picked out a couple of case studies from our portfolio of workshops and events.

Case study 1: The Craft of Academic Writing: Poetry as a vehicle for reflection and expression, by Martina Diehl

The research journey is, in part, about developing an authentic academic writing voice. Academic language can feel strange and daunting as the narrative needs to be coherent, transparent, rigorous, honest, and formal to ensure clarity and integrity. The story of the research can become a complex web of thoughts, arguments, and results based on experiments, explorations and literature. So, how can we untangle and tie these strings of the narrative together to create a coherent and authentic research story?

This workshop for PGR students was based on my doctoral work using poetic inquiry – a creative method for making meaning from research data by writing data poems as a method of analysis.

When I started my PhD, I would often copy the academic writing voice of the academics I was citing. I felt like I couldn’t be me in my writing, and it was through being given the courage to ‘take more responsibility’ for bringing ideas and concepts together, that I was able to piece together an authentic and academic narrative. As I observed and listened to other researchers, I realised this struggle between the academic and authentic was a common concern. I originally designed a workshop on using poetry to play with language to reflect and express research creatively and critically, which led to further workshops that included poetry writing activities.

In 2019 I attended the NATE Conference (National Association for Teachers of English) and participated in a workshop facilitated by the poet Luke Wright which introduced the format of the ‘I Am’ poem. I adapted this type of poem to explore (part of) the research through a new lens.

In these workshops, participants start their poems with ‘I Am A…’, followed by the research subject/topic. For example, ‘I am a protein’ or ‘I am an electron’, and through that lens they can then explain what their research aims to do from a new perspective.

There are three rules to this form of poetry writing:

- It starts with ‘I Am A…’

- It has rhythm, and the rhythmic breaks in the poem have a purpose

- The writing of the poem has a time limit (5-10 minutes) to prevent the ‘inner-critic’ from becoming too loud.

This example poem represents some student survey and teacher interview data from my own doctoral research:

Why should I?

I am a secondary school student

I think poetry is dull and boring

There’s no point just

Annotations, analyses,

My parents don’t use it,

My siblings never needed it,

Why should I?

It can also be creative

Help us find innovative ways to think,

Give us a deeper understanding of world matters

To make meaning,

Develop vocabulary, language,

Understanding culture…

But not in English schools,

Maybe in some Dutch schools?

We just learn poems we

Can’t relate to

Written by dead, white middle-class men

About power, conflict and

Mainly World War 1.

They’re all dead,

They’re not me.

It’s just to pass an exam

What’s the point?

Case study 2: Drawing out the why: creative tools for research thinking by Sarah Dodds

In this this workshop participants are guided in using visual and tactile methods—such as drawing, collage, and pictorial metaphor to uncover the deeper ‘why’ behind their research questions and consider how integrity shapes their scholarly journey.

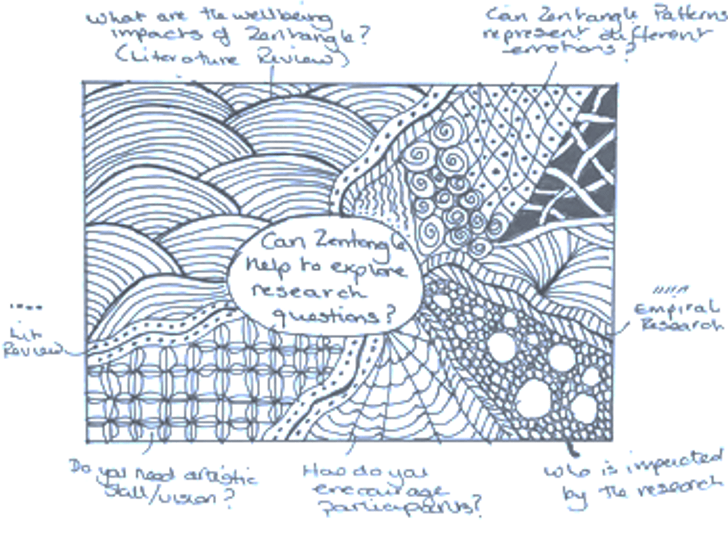

One of the techniques used is a Zentangle a method of purposefully doodling to promote relaxation, wellbeing and focus on the research tasks ahead (Nordell, 2012; Hermanto et al., 2025).

Zentangle can also be used as a thinking technique to explore different aspects of research and can promote reflective practice (Wallace, 2020). Participants were asked to consider their research questions and use Zentangle techniques to represent those questions. To begin the task, students were shown how to draw several different Zentangle patterns. Each Zentangle (example in Figure 2) starts with a string, a curved and looped line drawn onto the card to form sections. Each section is then filled with a repetitive pattern, the tangle, in a slow, measured and methodical way. They were also given a sheet with further patterns from which they could take inspiration.

Each participant was asked to draw a looped line on a postcard and then fill each section with a pattern which reflected their research question. Once complete, they were asked to present their postcard explaining why they had chosen the pattern. Some included dark, heavy patterns for research questions they were struggling with, light patterns for questions not yet tackled or which were progressing well. The participants agreed that drawing helped them identify those areas of research which needed more reflection and thought.

Making space for play in a changing academic landscape

Promoting a playful approach to Researcher Development may seem frivolous at a time when universities are consolidating, restructuring, and reducing expenditure. However, we believe that playful experimentation and the ability to communicate ideas with a creative, critical and reflective perspective are fundamental contemporary research skills.

Providing a varied programme of events where playful and creative activities sit alongside, and are sometimes integrated into, more traditional workshops have a range of benefits for our researchers.

Giving ‘permission’ to play, to explore and experiment, and perhaps fail (safely) in a supportive environment can be empowering. Paraphrasing one of our international PGRs following a poetry workshop: For the first time they felt able to bring their identity into their English academic writing, in a way they hadn’t thought possible.

The informal, small group, discursive nature of sessions where everyone is experimenting outside their normal comfort zones (whether this is through poetry, storytelling, podcasting or zentangle doodles) encourages sharing and imaginative freedom.

Research is all about having, exploring, and communicating ideas, and through a playful learning approach researchers can begin to be brave in the imagining and reimagining of their research stories.

Leave a comment